This month marks 60 years since the student free speech movement was born at the University of California Berkeley. Ideally, it should be an opportunity to look back with pride at how far we’ve come since then.

But perhaps we haven’t come as far as we think, and maybe we’re even moving backward, as this Andy Kessler piece in the Wall Street Journal points out, given how tenuous, fragile, and besieged campus free speech seems today.

Indeed, one couldn’t be faulted for wondering, as one scans American college campuses today, with their trigger warnings, safe spaces, shout-downs, speaker cancellations and enforced conformity of speech and thought, whether the movement born at Berkeley isn’t dying if not dead.

UC-Berkeley Chancellor Rich Lyons claims that the campus free speech movement is alive and well at the school, on the 60th anniversary of its storied founding: https://news.berkeley.edu/2024/10/01/a-message-from-chancellor-lyons-on-the-60th-anniversary-of-the-free-speech-movement/… But others, including Kessler, believe it’s been betrayed by some of the same people who put “the movement” in motion.

Here's Kessler’s recap of how it all began back in 1964:

“Sixty years ago this month, the Free Speech Movement was born at the University of California, Berkeley. How is that working out?

In mid-September 1964, Berkeley’s dean of students banned tables and political activity along the Bancroft strip, a 26-foot stretch of university-owned sidewalk near Telegraph Avenue down from Sproul Plaza. I walked around the area last week and found, almost paradoxically, a capitalist BMO Bank, a Marxist-glorifying César Chávez Student Center and a techno-optimist Open Computing Facility

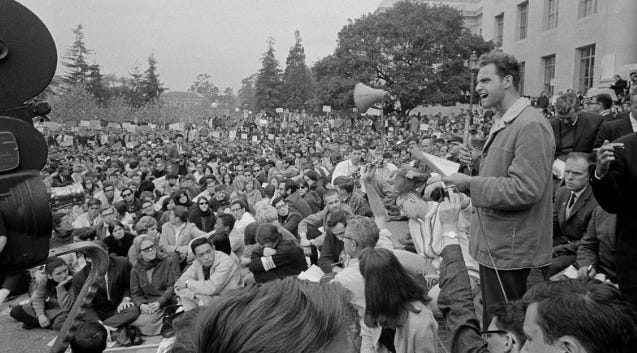

Berkeley’s 1964 students protested the table ban. On Sept. 30, five students were cited. More than 400 insisted that they were also responsible and should all be cited too. They then staged their first sit-in inside Sproul Hall, Berkeley’s administration building. The next day, tables were set up outside Sproul Hall. The police were called and arrested Jack Weinberg. Some 200 students surrounded the police car. Speeches began as thousands assembled. Mario Savio emerged as a Free Speech Movement leader.

With the cop car still surrounded by late afternoon on Oct. 2, 500 police officers were on hand at the university. A six-point agreement was reached with the university president, and the protests ended. As is typical of universities, committees were formed. A six-week ban on tables was instituted and Mario Savio and others were suspended. But by mid-November, the tables were back, and 3,000 students marched around campus.

The students eventually won concessions from the school and prevailed against The Establishment, as personified by then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan. And the rest, as they say, is history — albeit history with an odd twist, given the comparatively tenuous state of campus free speech today.

Writes Kessler:

“Sadly, campus free speech has been lost since 1964. Savio’s speech has been an inspiration for civil disobedience, most recently at Columbia and elsewhere this spring. Even peaceful protests these days are now more about what you can’t say. What started as safe spaces and trigger warnings are now almost always one-way actions, cancellations and censorship of ideas progressives don’t like.”

There’s irony in the movement’s moribund state, given how the speech advocates of old often seem to be leading the reversal. No longer are they rebels and “radicals” battling “the establishment.” These days they are the establishment. And it’s on their watch that this strange and alarming back-peddling has taken place.

Many of the same progressives who claim a radical pedigree dating back to Berkeley today loudly bang the gong for censorship of views they don’t like, notes Kessler, ticking off a list of prominent leftists who support muzzling opponents.

Why does the movement seem to be moving backward? Perhaps a power shift explains it.

The radicals of 1964 were proud outsiders and underdogs, doing battle against “the man.” Today they’re entrenched insiders, who have burrowed into and taken control of institutions they formerly scorned. The dominance they enjoy gives them the clout to crush and cancel ideas or views ( or individuals) with which they disagree. And today’s “liberal establishment” hasn’t been shy about using its power to blot out dissenting voices and ideas — to impose and enforce a campus monoculture that slavishly mirrors their worldview.

Whether the 60th anniversary of the Berkeley protests will jog the conscience of those who abandoned their former positions on free speech is doubtful, given the subdued attention this is getting in academia. Hearkening back to those glory days just highlights the embarrassing contrast to what’s seen on campus today. But ASFA alumni haven’t forgotten. And we’re hoping the anniversary will remind erstwhile free speech stalwarts that the revolution they sparked is being reversed and betrayed — and often by the same people who gave the movement its early momentum.